New York City, and therefore the Bronx, has not always been as safe in terms of health as it is today. Previously, the public healthcare system was underdeveloped. Private medicine could not help everyone. That’s why the city often experienced various epidemics that killed hundreds and thousands of its residents. One of these diseases was cholera. Among the many solutions that helped stop the epidemic was the construction of the Croton Aqueduct. It was built in the Bronx. Read more about the disease and the fight against it on i-bronx.com.

The history of cholera

According to thevillagesun, little was known about the diseases that threatened New Yorkers and the surrounding areas, such as Westchester County, which now forms the basis of the Bronx, until the mid-nineteenth century. At that time, a typical inhabitant of the planet tried to have many children as they realized that some of them would die in childhood. In 1850, the average life expectancy of a New Yorker was less than 21 years.

Almost 40% of children under 5 died. That is why families had about 6 children. This was the only way to save the human race from extinction. After all, yellow fever, scarlet fever, typhoid, diphtheria, meningitis, influenza and cholera attacked and destroyed New Yorkers.

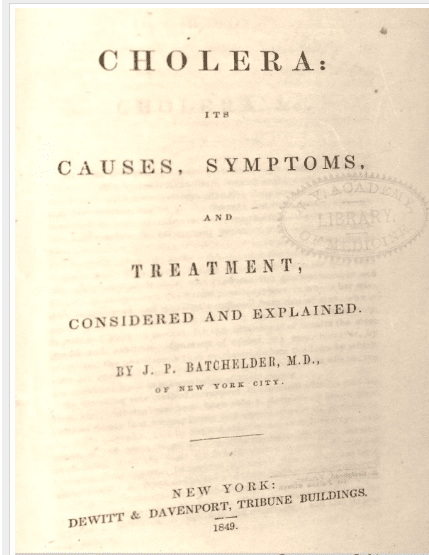

One of the most deadly diseases is cholera. Its causative agents are river microorganisms. Over time, they got into the river water. Here it spread well through sewage and feces and infected more and more people. The spread of the disease began in Asia. Then, Europe, the United Kingdom and, thanks to lively trade, North America were hit. It happened in 1832.

Photo from https://nyamcenterforhistory.org

What contributed to the emergence of cholera in New York in the first half of the nineteenth century

NYC was founded in 1626. In the 1930s, it already had a population of 250,000. They lived mainly in Manhattan. Food was received from the towns and villages that spread around it, including Westchester, Yonkers, Eastchester and Pelham. They would later form the basis of the Bronx.

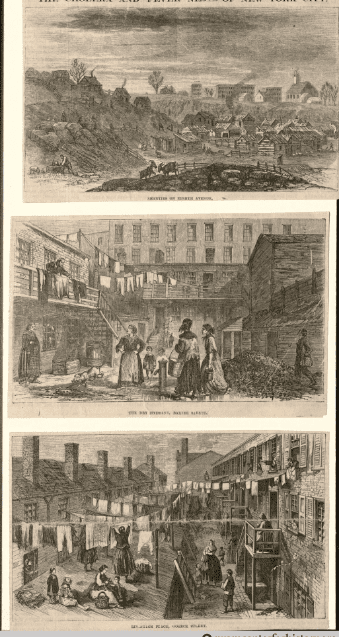

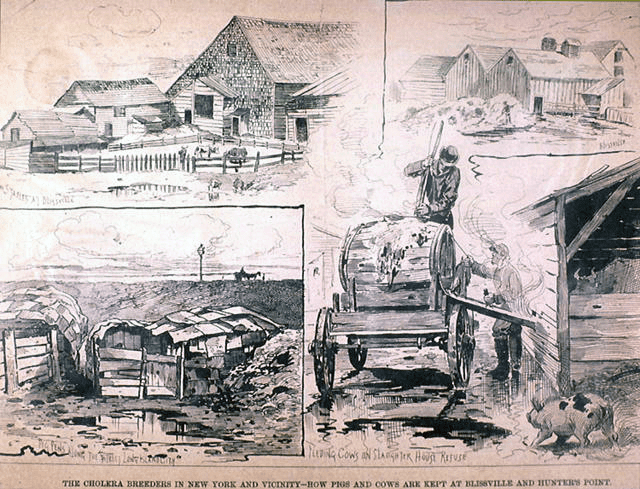

The city was dirty at that time. Garbage was collected by pigs and dogs, who simply ate it. People lived next to animals on streets made of dirt and manure. No one was prepared for the epidemic, not even doctors. Five Points, the neighborhood where the epidemic broke out the worst, was a slum at the intersection of five streets north of City Hall. Back then, African Americans and Irish Catholic immigrants lived there together. Today it is Chinatown and Foley Square. “All that is loathsome, drooping and decayed is here,” Charles Dickens wrote. Martin Scorsese in his movie Gangs of New York showed what the area looked like during the epidemic.

The city was not interested in resolving the issue of garbage collection, cleaning the streets of pigs, or establishing a quality water supply. The money that was allocated for this disappeared into the pockets of people close to the mayor. Water was taken from wells. Thus, when the epidemic hit, the city was doomed.

Photo from thevillagesun.com

Cholera in New York and the surrounding area in 1832

In the UK, the city of York suffered the most from cholera. But merchants who traded with the US tried not to talk about the disease as they realized that it would affect their business. NYC leaders also wanted to reduce the scale of the threat.

At that time, no one was comprehensively studying the disease. But there were theories about its origin. It was reported that this disease affects only the poor (remember, when AIDS appeared, they said it was a gay disease, or when COVID appeared, all the thunder and lightning flew at the Chinese).

It was also reported that the source of cholera was the stench of garbage and rotting sewage. The positive aspect of the second version was that its supporters believed that cleaning the streets of garbage and repairing the sewage system would help defeat the disease. At the same time, cleaning the streets would not have helped completely. After all, cholera, along with untreated sewage, penetrates wells and infects people who think they are drinking clean water. The filter system was of little help here.

Photo from thevillagesun.com

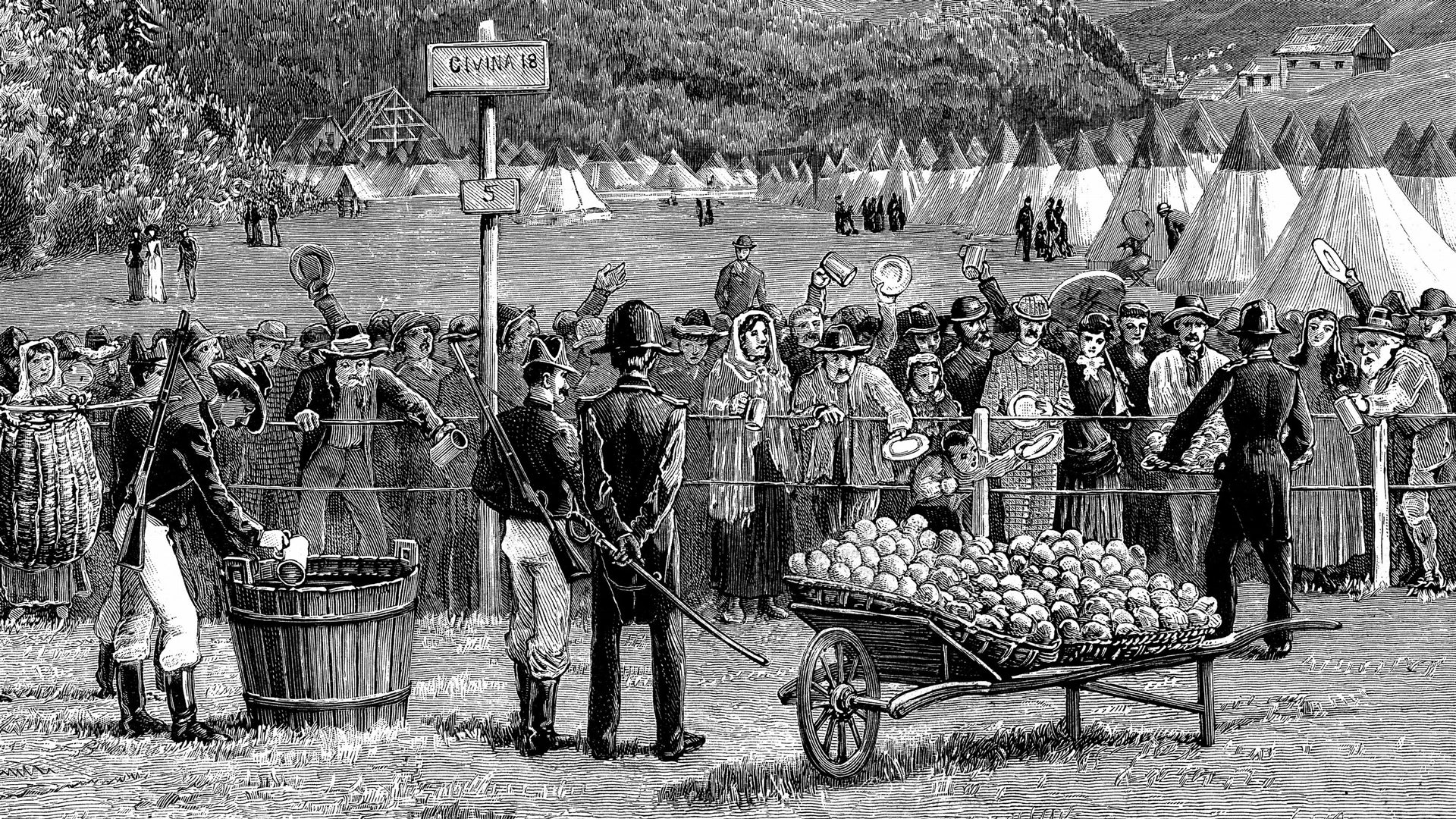

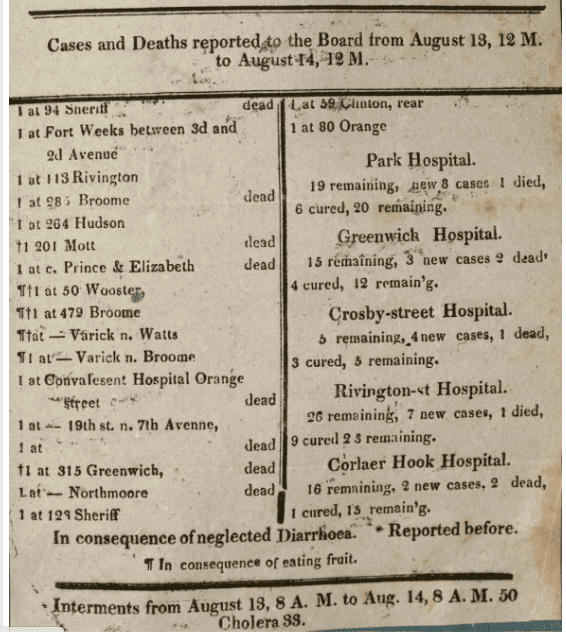

The epidemic hit the city in June 1832. Doctors worked for free, seeing patients. But they could not cope with the influx of visitors. Moreover, the treatment was useless: cholera, when it enters the stomach, causes diarrhea. The latter causes dehydration and can kill in a few hours. Nevertheless, patients came to Park Street, Greenwich Street, Crosby Street, Rivington Street hospitals, the Almshouse and other places.

The rich believed that the quarantine was a hindrance to business and should be canceled. The yellow press even reported that the cholera had come to stop the panic that could have hindered business. The poor had different views. They believed that doctors, who were looking for corpses for autopsies, were to blame for the spread of the disease, as well as the inaction of the authorities.

Photo from thevillagesun.com

Consequences of the disease

In July 1832, 1,800 people died. Upon hearing about the first victims, wealthy citizens rushed out of the city toward Greenwich Village and Westchester County (remember that it is now the Bronx). John Pintard, the founder of the New York Historical Society, believed at the time that the sooner the patients died, the sooner the disease would disappear. Kenneth T. Jackson (historian) wrote that if a person got cholera, it was their fault.

In August, another 1,200 people fell ill and died. In September, it became colder and the epidemic declined. In total, 3,500 people died. The disease paused, but did not disappear, as some believed.

What was done to eliminate the consequences and prevent cholera in the following years

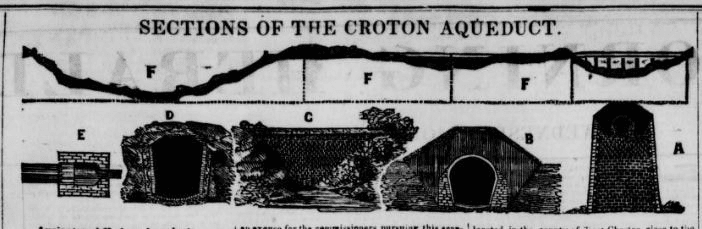

- First of all, the construction of the Croton Aqueduct, which ran through the modern Bronx and connected to Harlem via the High Bridge, was started to fight the disease. It was completed in 1842. The wells were closed and it was forbidden to draw water from them. Subsequently, the water supply systems that ran through the Bronx (in particular, the New Croton Aqueduct), sewage and garbage disposal improved. This led to a steady increase in life expectancy and a perceived victory over infectious diseases.

- In 1849, more than 20,000 pigs were driven off the city’s streets. If the public was against such a step before the disease, after it people silently obeyed.

- In 1866, the NYC Metropolitan Board of Health was created. Its inspectors went to homes to burn the clothes of those who died of the disease, spread lime and instruct survivors on sanitation.

- Treatment at the time was based on the use of large doses of laudanum (morphine), calomel (mercury) as a binder and laxative and camphor as an anesthetic. Poultices of mustard, cayenne pepper, hot vinegar, opium candles and tobacco enemas were also used.

- While Protestants fled the city, Catholics remained. The role of Catholic nuns and priests who cared for the sick was especially significant in overcoming the disease. There was even a certain decline in anti-Catholic sentiment.

Photo from thevillagesun.com

Thus, through epidemics that have killed thousands and thousands of people, humanity has realized that it is necessary to think about the issue of proper food consumption, clean water and cleaning up garbage and excrement. However, as we can see, at the beginning of the 21st century, epidemics continue to appear. Can we say that we have learned the lessons of history? As long as we are ruled by ignorant people, propagandists of theories that have nothing to do with science and education, people who put money and power first, we give diseases the freedom to rule over us.