There are people who believe that all professions are divided into male and female, and there are those who break these stereotypes. Esther Lederberg, the daughter of Jewish immigrants from Ukraine, who spent her childhood in the Bronx and later became a pioneer in the study of bacteria in world science, was one of them. Read more about E. Lederberg on i-bronx.com.

Childhood and learning Hebrew

According to whatisbiotechnology, Esther Miriam Lederberg was born on December 18, 1922, in the Bronx. Her parents, David Zimmer and Pauline Geller Zimmer, were originally from Bukovyna. In the nineteenth century, it was a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In the 1920s, it was part of the newly formed Kingdom of Romania. In the twenty-first century, it is Ukraine’s smallest region. After emigrating to the United States, David Zimmer opened a printing house in the Bronx to support his family.

The future scientist’s childhood was spent on the streets of the Bronx during the Great Depression. It was a period characterized by unemployment, food shortages and a lack of a predictable future. Therefore, the girl recalled those years as extremely hungry. Often, she would eat only a piece of bread for lunch, which was flavored with tomato juice. Esther was the eldest child, so she had to look after her younger brother.

Living in the Bronx, which at the time was a place where different ethnic groups lived densely: Irish, German, Italian and Jewish, created opportunities for everyone who wanted to develop. The only obstacle was gender. All roads were open to men. For women, artificial obstacles were created. This was the case with Esther. She was close to her grandfather. When he tried to teach his boy grandchildren (Esther’s cousins) Hebrew, he realized that it was difficult.

At this time, Esther became interested in Hebrew and asked him to teach her. This was unusual as only men learned Jewish language. At the same time, Esther quickly learned the language and delighted her grandfather when she performed all the readings for the Passover Seder.

Education at school and college

Esther studied at Evander Childs High School (now an educational campus of the same name in the Gun Hill neighborhood of the Bronx). The school got its name in honor of its principal, Evander Childs, who died in 1912 at his desk. The school is famous for the fact that in 1938 James Michael Newell painted 8 murals there dedicated to the history of Western civilization. In 2008, the school was divided into 6 smaller units.

But let’s go back to Esther. She graduated from high school at the age of 16, which means it was 1938, and went to Hunter College. It was an urban community college for those who did not have the means to attend private schools. Esther was lucky here as she not only studied but also managed to win a scholarship.

Initially, she planned to study French language and literature. But, at some point, the girl decided to change her mind and take up biochemistry. What caused this change is unknown. Also, college professors tried to dissuade Esther from this decision. They believed (and, as we will see later, they were right) that it would be difficult for a woman to make a career in such a field.

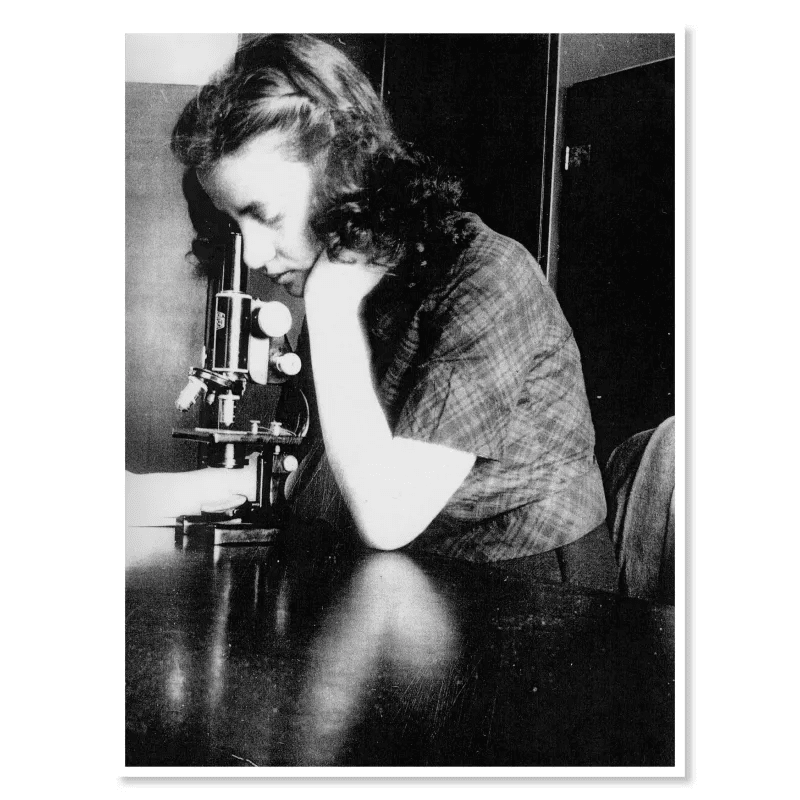

Esther did not change her mind. Thanks to it, the world got a revolutionary scientist in the field of bacteriology. Along with her studies, Zimmer worked at the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx. Here she studied mold. In 1942, Esther received a bachelor’s degree in genetics with honors.

Scientific career

After graduation, the scientist went to work for the U.S. Public Health Service, based at the Carnegie Institution of Washington’s Department of Genetics. There, she began to study bacteria. Later, the woman wrote her first paper on increasing the efficiency of penicillin cultivation.

Next, in 1944, she attended Stanford, where she received a scholarship and a master’s degree upon graduation. In 1945, Esther was an intern at Stanford University under Cornelius van Niel at Hopkins Marine Station. There was not enough money for everything, so E. Zimmer had to work as an assistant in the laboratory.

This gave her the right to have free housing. She also washed her mistress’s clothes to earn money for food. When food was scarce, she was forced to eat frog legs that she took after experiments in the laboratory.

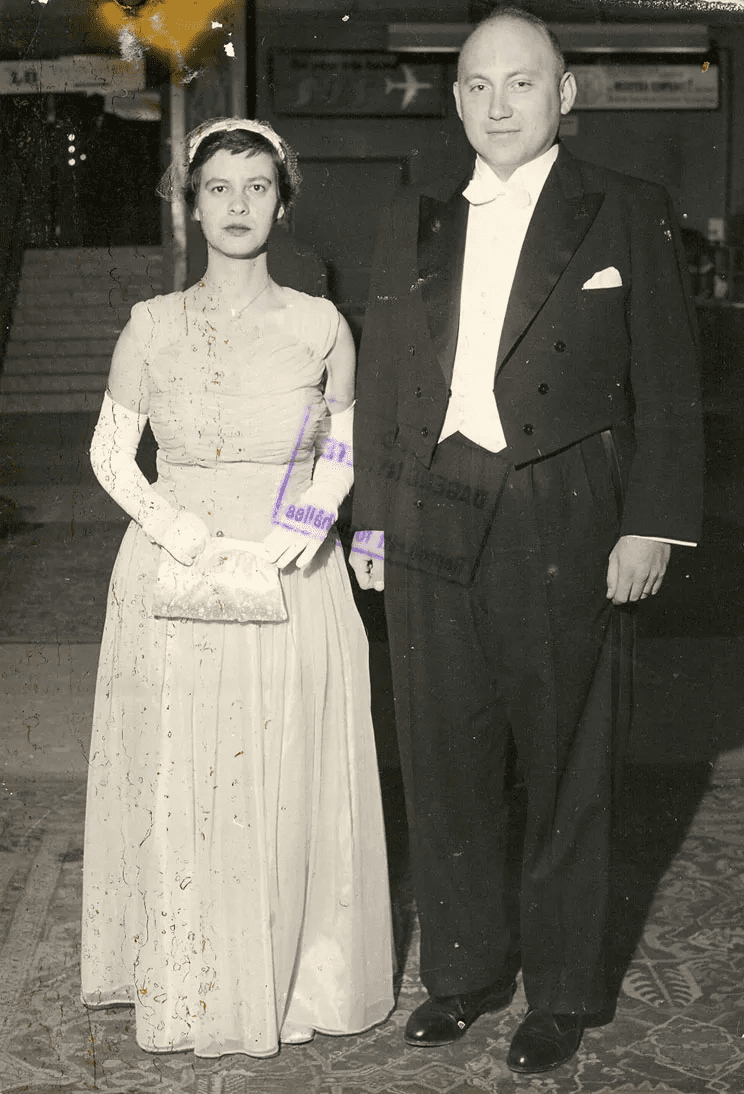

In 1946, she married Joshua Lederberg, who had studied under the same supervisor as her, namely Edward Tatum. In 1947, Esther moved to Wisconsin, where her husband was a professor at the local university.

He was a man with a lot of ideas. She was a first-class experimenter who could do boring and monotonous work in the laboratory. Here, the woman was not paid a salary. However, she got the opportunity to work with her husband and study the adaptation of bacteria to drugs. They proved that mutations in bacteria occur so quickly that they can be seen in the laboratory.

In 1950, Esther defended her thesis here on Genetic control of mutability in the bacterium Escherichia coli (this bacterium is found in our intestines).

Discrimination at work and attempts to further advance in her career

After World War II, Esther looked for work that she thought would be more financially attractive to women. She was convinced that the end of the war would bring men back. Thus, women would be pushed into the background again. She also saw that research positions were more suitable for women and could create opportunities to advance her scientific knowledge.

While working in Wisconsin, Esther, despite her experience, was still unable to obtain a permanent research position. She had to be in the shadow of her husband. Thus, she was faced with a dilemma: to be married to Joshua and not be recognized as a scientist or to become independent. Esther’s character also hindered her work. She did not value herself and believed that she did not devote enough time to her work. When her husband received an award in 1953 and tried to share it with her, he heard that there were several other people who could claim the prize.

In 1959, J. Lederberg went to work at Stanford. Esther began working at the Department of Microbiology and Immunology. To do this, she had to write to the dean of the medical school and draw attention to the lack of women in the school.

In the following years, Esther continued to fight for recognition as a scientist. In 1968, she divorced her husband. In 1974, the woman became an associate professor. But it was still a demotion. Her contract was open-ended at the time and depended on the research grants she received.

E. Lederberg’s achievements, awards and last years of life

We can talk about E. Lederberg’s life and achievements for a long time. Let’s try to list her main accomplishments:

- Discovered the lambda phage, a bacterium used in genetics

- Studied the relationship between transduction and lysogeny of lambda phage

- Investigated the fertility factor in bacteria

- Together with her husband, she investigated the genetic mechanisms of specialized transduction

- Invented the technique of copying bacteria.

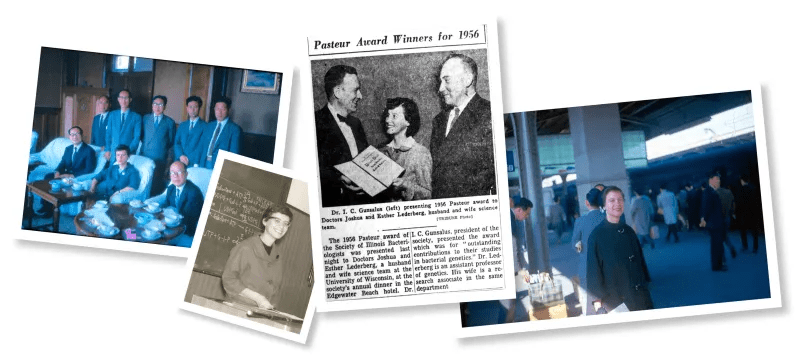

In 1956, Esther and Joshua Lederberg were awarded the Pasteur Medal for their achievements in bacterial genetics.

Esther died on November 11, 2006, from pneumonia at Stanford at the age of 83.