A somewhat eccentric and obsessive scientist who was constantly tinkering with flies in his labs, and a winner of numerous global awards and honors in the fields of physics and biology. All of this describes one person—Seymour Benzer, the subject of this article on i-bronx.

A Gift That Changed a Little Boy’s Life

The future scientist was born in the South Bronx in 1921 to a family of Polish immigrants with Jewish roots. The boy grew up surrounded by three sisters but preferred to spend time alone. Seymour was a good student, very quick-witted and curious. In an interview, his friend Jean Weigle called him a “two-yolk egg”—an old expression used for something truly rare and unusual.

One year for his birthday, Seymour was given a microscope. “It opened up a whole world to me,” Benzer recalled. He would sit for hours with this incredible instrument, examining everything that came into his hands—sand, stones, dirt, paper, food, flies, and worms.

But the boy never neglected his studies; they were always a priority. In 1938, Seymour received a Regents Scholarship to Brooklyn College, becoming the first in his family to enter a higher education institution, where he began to study physics in depth.

Personal and Professional Adulthood

In college, Seymour continued to study enthusiastically but also started to notice girls. There, he met Dorothy Vlosky—a medical student—and immediately fell in love. The feelings were mutual, and very soon the young people, both 21, got married. Straight from their wedding, the couple drove to Lafayette, Indiana, where Seymour planned to pursue a graduate degree in physics at Purdue University. “We left the guests dancing while we drove to the train to Indiana,” Seymour recalled. “We wanted to have at least a little honeymoon, and there was little time left before classes started.”

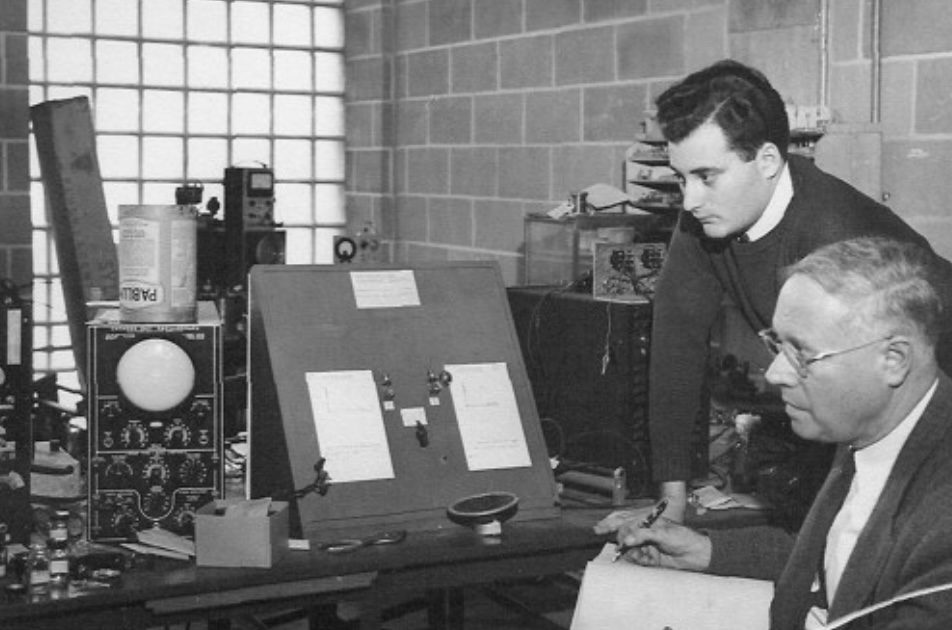

At Purdue University, Seymour joined Karl Lark-Horowitz’s team, which was working on a large program to improve germanium semiconductors for radar systems. Such projects were very important during the war that was raging in Europe. It was here that Seymour Benzer was finally able to fully demonstrate his outstanding knowledge and skills. He discovered that germanium crystals with small tin impurities made excellent rectifiers: they allowed current to flow in one direction but blocked the reverse flow, even at a high voltage of over 100 volts.

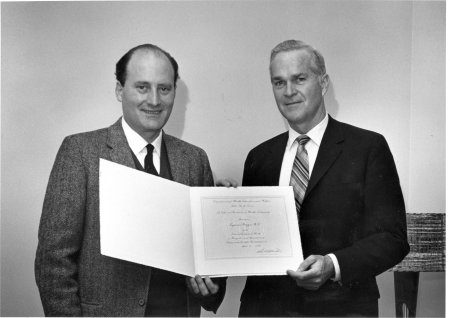

Benzer patented the results of his research, and several industrial laboratories began to actively implement the new material in their work. Three years later, it was precisely this discovery of the properties of germanium and tin crystals by Seymour that helped scientists Walter Brattain, John Bardeen, and William Shockley defend their dissertations and create the first transistors at Bell Labs, for which they received the Nobel Prize. Benzer was present at the celebration of the technological breakthrough at Bell Labs, received many words of thanks and admiration, and the inventors invited him to collaborate, but by then, Seymour had lost his passion for physics. His heart had been ignited by a new passion—biology.

Read about another famous professor from the Bronx who dedicated her life to the study of viruses and bacteria in this article.

From Physicist to Biologist

Seymour became fascinated with the new field of molecular genetics. Lark-Horowitz saw that Benzer was too distracted from physics, so he supported the scientist’s desire to switch to biology, even though Seymour had several promising job offers from physics departments. But Lark-Horowitz felt that this researcher and inventor was capable of achieving much more in the field of biology, so he created the most comfortable conditions for Benzer to retrain. He offered him an associate professor position at Purdue University and also gave him the opportunity to take a sabbatical for postdoctoral research in phage genetics. The sabbatical was initially planned for one year, but it stretched into two, three, and eventually four years. The dean of the department was outraged by Benzer’s long absence, but Lark-Horowitz took full responsibility and persuaded the leadership not to interfere with Seymour’s work.

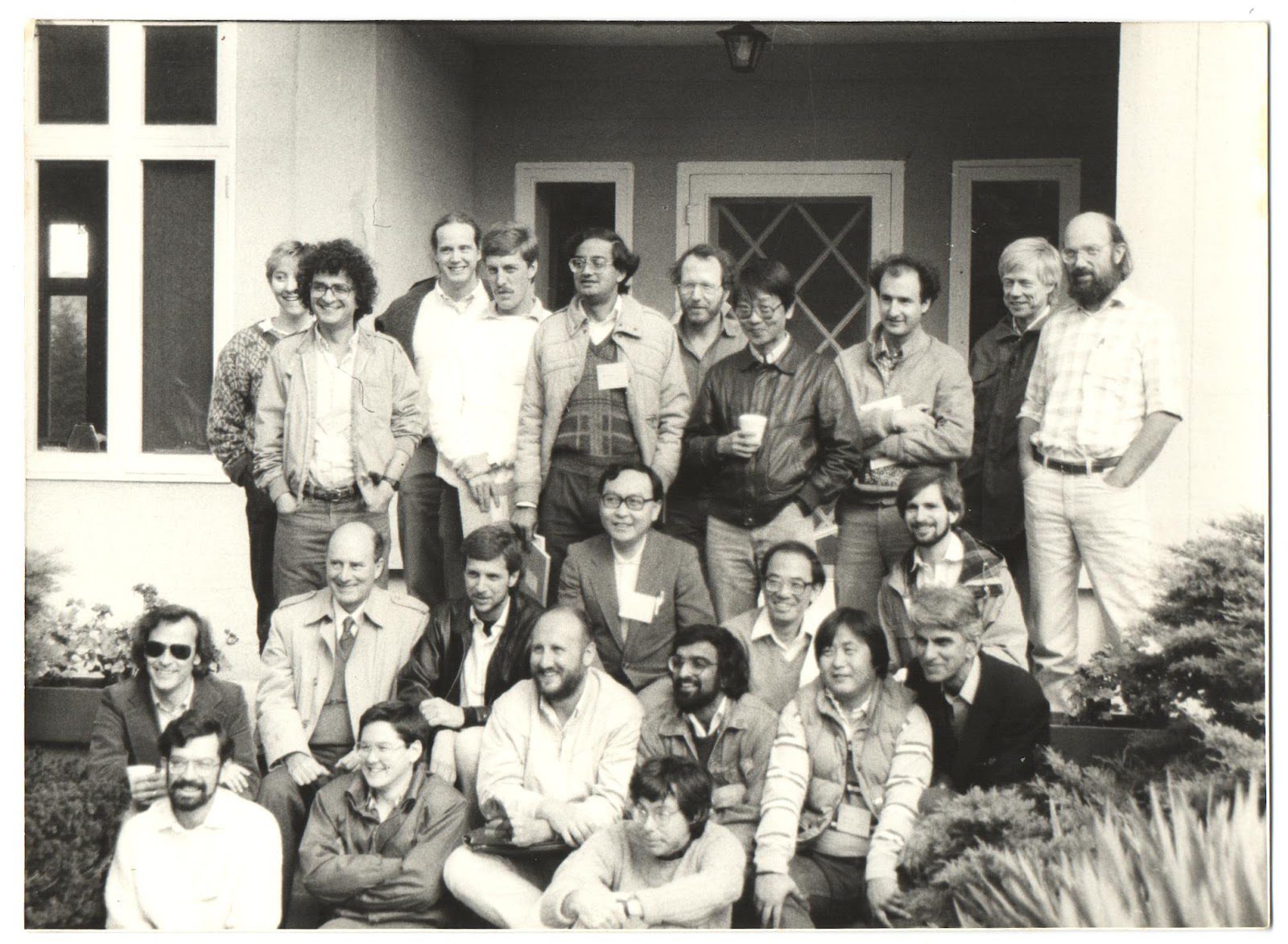

Benzer always recalled this period of his life with warmth and gratitude. Despite being able to gain a fundamental understanding of phage genetics during this time, he and his wife were also able to immerse themselves in the community of early molecular biology pioneers. Seymour met and had close ties with Max Delbrück and his colleagues at the California Institute of Technology, as well as with André Lwoff and his team at the Pasteur Institute.

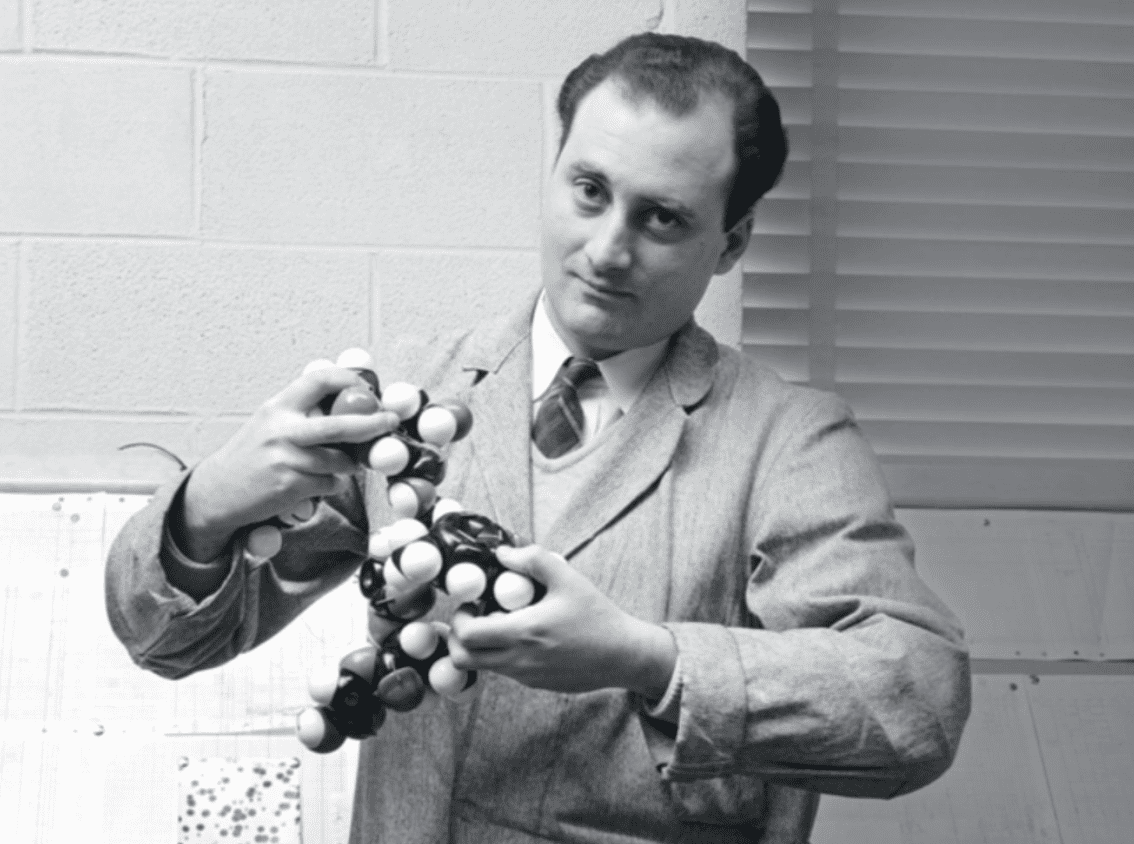

Diving into Genetics

Benzer returned to Purdue University only in 1952, but with research that was groundbreaking for the time. He had found a way to study the physical nature of the gene. The first attempts to do this were made by Alfred Sturtevant, who used the fruit fly to demonstrate that genetic factors are located in a specific order on chromosomes, based on the principle that the lower the frequency of recombination between them, the closer they are to each other. Hermann Muller added to this the concept of the “gene,” a term he coined to describe the unit of heredity that can be separated from others through recombination. But what is a gene from a physical standpoint? Is it made only of nucleic acids, or is it part of a protein? Is it simply a linear segment of DNA or something more complex?

It was these questions that Seymour Benzer answered in his work. He gave the gene a physical meaning. In his book, Frederic Holmes noted that Seymour was the scientist who “more than any other single individual enabled geneticists to adapt to the molecular age.”

People and Flies

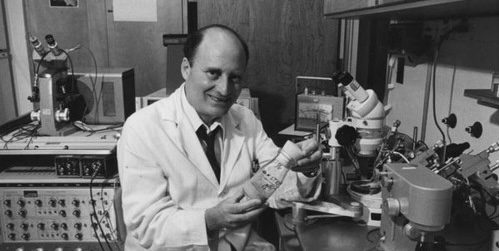

Benzer continued to work in the biology department but couldn’t find time to study a phenomenon that had long bothered him. Seymour and Dorothy had two daughters who were dramatically different from each other both in appearance and personality. In 1966, Benzer couldn’t take it anymore and took another long sabbatical from the university to finally conduct a large-scale study in Roger Sperry’s lab at the California Institute of Technology.

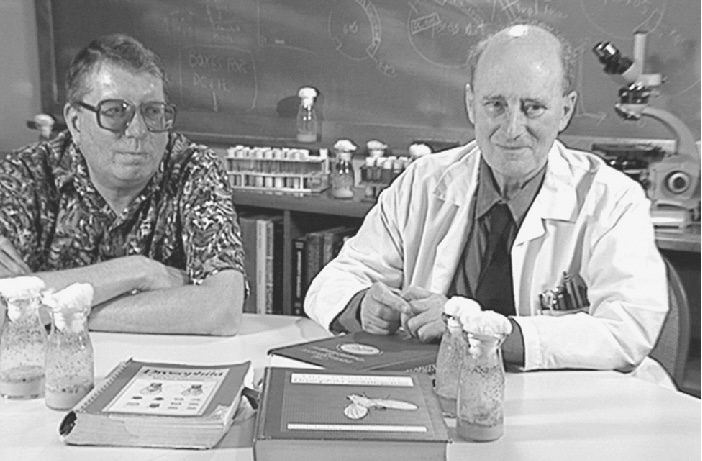

Seymour chose the fruit fly, Drosophila, as his research subject, explaining that for genetic experiments, it’s important to have an organism that can be worked with at a population level. For example, if you conduct experiments with rats, obtaining statistically significant results would take a lot of time, while with flies, you could quickly get large amounts of data.

One of the first behaviors he began to study was phototaxis. He found that when flies were tapped to the bottom of a test tube, they would run toward the light—this phenomenon is called fast phototaxis. Seymour began experimenting with mutagens and selecting mutants based on their reaction to light. Many mutants looked healthy but didn’t react to light. He discovered that some of them were blind due to defects in their photoreceptors, while others had problems at the brain level. He also found mutants that had seizures or were paralyzed after being tapped on the test tube. Using a variety of screening methods, Seymour and his team of neurogeneticists uncovered a wide range of behavioral changes linked to genetic changes.

When Benzer’s mother learned about his research on the fly brain, she initially doubted the wisdom of this pursuit. She once pulled his wife aside and said:

“Is that how he makes a living? Tell me, Dotty, if Seymour is going to study the brain of a fly, don’t you think we should study his brain?”

But today, neurogeneticists around the world are working based on those very studies.

Eccentricity and Genius

Those who worked in Seymour’s lab were inspired by his creativity, humility, and great sense of humor. Sometimes Benzer did strange things: he’d bring something unusual to lunch, like fermented fish or chocolate-covered larvae. He could be seen warming up his lunch of cow’s udder or bull testicles on a Bunsen burner or playing with a keychain shaped like an eyeball. Once, he missed an important meeting to attend the funeral of a Hollywood actor’s dog.

Nevertheless, Seymour received countless prestigious awards in biology, including the Gairdner Foundation International Awards, the Albert Lasker Award, the Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize, the Harvey Prize, the Dickson Prize, the Rosenstiel Award, the Karl Spencer Lashley Award, the Ralph Gerard Prize, the Crafoord Prize, the Passano Award, and the Bower Award.

In his final research, Benzer found mutants that significantly extended the lifespan of fruit flies, one of which he named “Methuselah.” Many hoped that Seymour would be able to unlock the secrets of aging, but he died of a stroke at the age of 86, leaving behind a huge legacy of discoveries and inspiration for future generations.

Read the article about folk medicine in the Bronx by following this link.