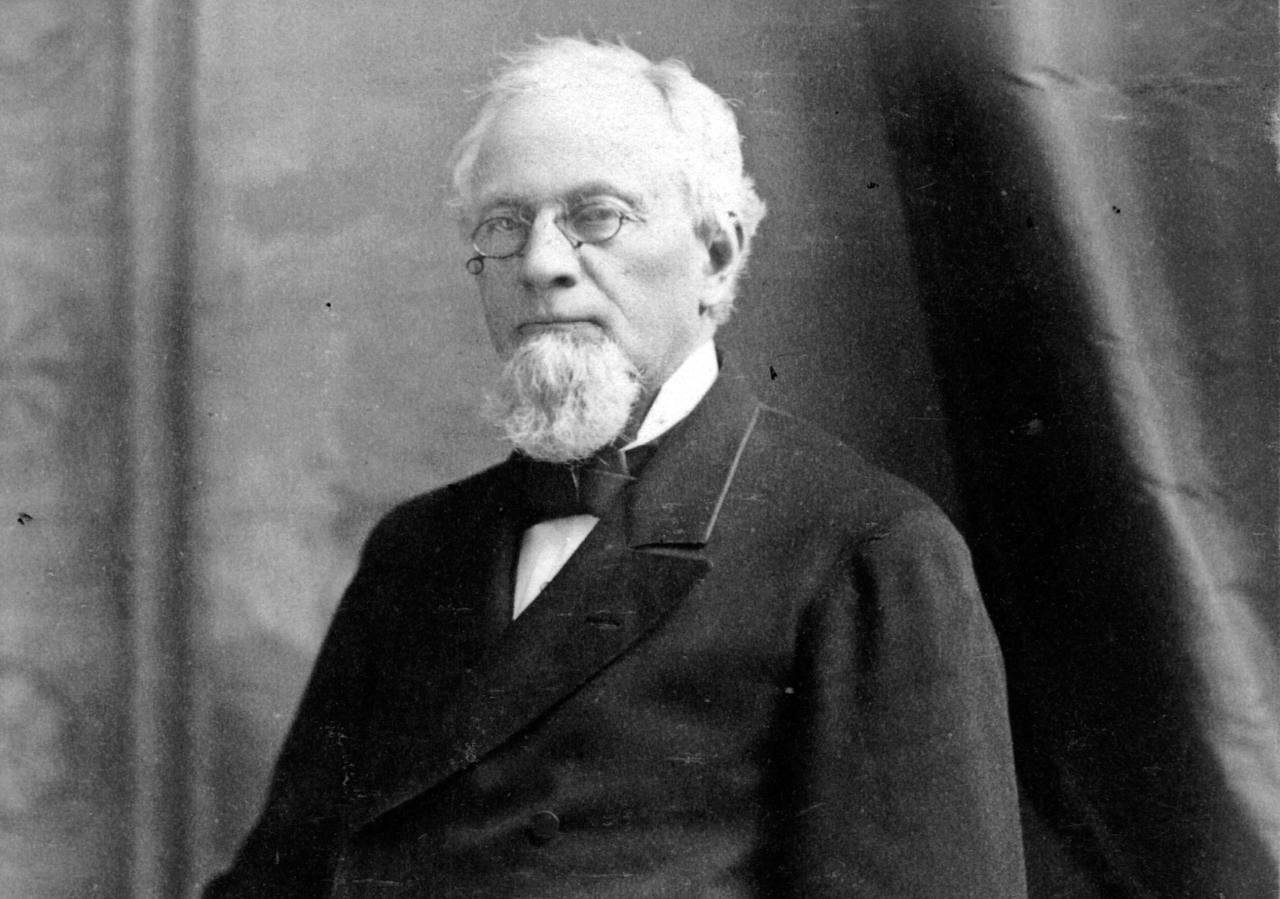

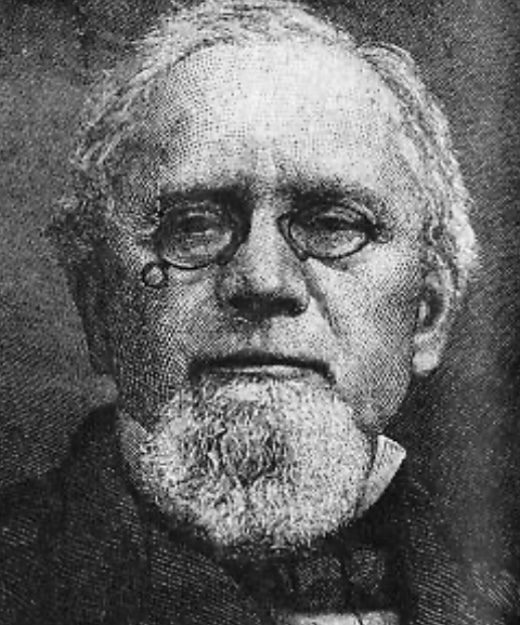

This American inventor created sleeping and comfortable passenger cars, which significantly raised the standard of comfort for railroad travel in the 19th century. His Wagner Palace Cars became a true symbol of luxurious journeys of that era. But, ironically, he died in a train crash near the Bronx while traveling in a regular, old car. Let’s explore the life and tragic death of Webster Wagner on i-bronx.com.

Origins

Webster Wagner was born on October 2, 1817, in Palatine Bridge to a family of German descent, among the region’s first settlers. His father and grandfather were both named John, while his great-grandfather, Lieutenant Colonel Peter Wagner, was a well-known partisan officer during the American Revolution. He was actively involved in border conflicts, had significant influence in Tryon County, and owned a fortified stone house known as Fort Wagner. Peter Wagner and his four adult sons, all committed to the Whig cause, were always ready to take on dangerous tasks in times of need. In those days, the surname was often anglicized as Waggoner, and it wasn’t until several generations later that the original spelling was restored.

The house with the wooden addition where Webster grew up stood on the Mohawk Turnpike two miles west of Fort Plain. His mother, Elizabeth Strayer, also came from an old German family that had settled in the area during colonial times.

Finding His Calling

In his youth, Webster Wagner learned the trade of a teamster from his brother, James. He later became his partner in a business that combined hauling with operating a furniture warehouse. The venture proved unprofitable, but Webster, having good habits, strong health, and determination, decided not to give up and to try again in the transportation field. In 1843, on the recommendation of a friend, Mr. Livingston Spraker, a director of the New York Central Railroad, he became a railroad station agent in Palatine Bridge. His duties included selling tickets, organizing freight shipments, and later representing the American Express company. He performed all these duties flawlessly, remaining a trusted figure even several years after his retirement.

In 1860, Webster stopped working as a railroad agent, but he had already started his own business related to the processing of grain and other agricultural products.

His Railroad Destiny

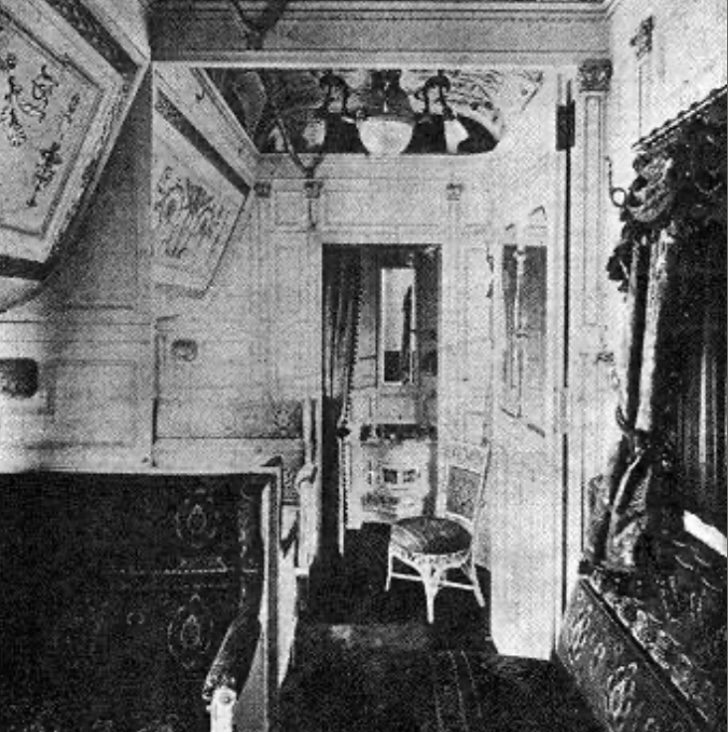

Webster Wagner was successful in business, but he missed the railroad. He was also haunted by the idea of creating sleeping cars that would provide passengers with a new level of comfort. In 1858, collaborating with George Gates, T.N. Parmalee of Buffalo, and Morgan Gardner of Utica, Webster Wagner finally built four renovated cars, each costing $3,200. For the first time, railroad cars featured beds with blankets and pillows. From then on, comfortable rail travel became a reality. On September 1 of that same year, the new cars began running on the New York Central Railroad with the support of the road’s president, Erastus Corning.

Initially, the project fell short of expectations due to ventilation issues. The ventilators located directly opposite the sleeping berths were dangerous if left open at night, while keeping them closed made the air stuffy. In 1859, Wagner solved this problem by inventing a raised roof with ventilation openings. This innovation not only saved his idea but also became the standard for all new passenger cars.

During the Civil War, Wagner’s cars became significantly more expensive but were distinguished by their durability, beauty, and comfort. They featured mattresses and full bedding, which was a marked improvement over earlier models. In 1867, Wagner created his first parlor car, or “palace car”—the first in the U.S. It quickly gained popularity among travelers, brought the inventor wealth, and provided thousands of passengers with comfort on their journeys.

Wagner’s cars spread to most major railroads in the country, and they were later adopted in Europe, where they were introduced by George Pullman.

Political Experience and Personal Life

In 1871, Webster Wagner was elected to the State Assembly. He won with a majority of about 200 votes in his district. The following year, Wagner became a senator for the 15th district, beating his opponent, Isaiah Fuller, by over 3,200 votes. In 1874, he was re-elected without opposition, and in 1876, he again secured a senatorial mandate, defeating Samuel Benedict with a majority of over 2,600 votes. In November 1877, Wagner received his fourth nomination for the position, once again convincing voters despite a strong opponent, the respected J. Scott of Ballston. He held his post in 1878 and 1879, winning by over 2,200 votes.

In politics, Wagner was known as a Republican with extensive experience in legislative work. His deep knowledge of the processes earned him an honored place on leading committees, and his younger colleagues often sought his advice on important matters. At the age of sixty, Wagner maintained robust health, sound judgment, and a readiness to continue serving the community.

Personally, Wagner was distinguished by his honesty, courtesy, generosity, and hospitality. He was a friendly, sociable person with strong family ties.

His estate in Palatine Bridge had well-maintained grounds, and the family spent winters in a spacious home in New York City. Wagner’s wife, Susan Davis, came from a respected family; her father, John Davis, was a master mechanic and carpenter. Wagner had five children—a son and four daughters, all of whom, except the youngest, Nettie, were married.

Tragic Death

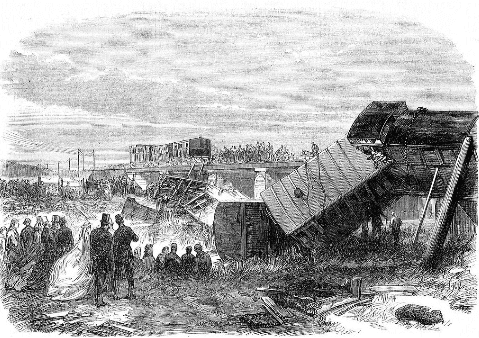

On January 13, 1882, on the New York Central Railroad line in the Spuyten Duyvil area (now part of the Bronx, New York), one of the most tragic accidents in American railroad history at the time occurred.

That evening, the Atlantic Express, a train traveling from Chicago to New York, was delayed due to bad weather and the need to attach extra cars. Upon arriving at the Spuyten Duyvil station, it came to a stop and remained on the track. At the same time, another passenger train was following on the same route.

Due to a faulty braking system and staff negligence, the following train failed to stop in time and crashed into the rear of the first train with great force.

As a result of the collision, the last two cars of the first train, including Webster Wagner’s private car, were crushed and caught fire. Wagner was in his car and died at the scene—his body was found crushed between the wreckage of the cars. This tragedy occurred just two weeks after the start of his sixth term as a New York State Senator.

A total of 8 people died in the accident, and dozens more were injured to varying degrees. This event became the largest railroad disaster in New York at the time and caused a significant public outcry.

The incident served as a signal to railroad companies and legislators about the need to strengthen safety measures on railroads, improve braking systems, and better organize train movements.

Legacy

Despite the founder’s death, the Wagner Palace Car Company continued to operate, remaining one of Buffalo’s largest employers in the late 19th century. The company’s massive factory spanned over 35 acres, employing hundreds of specialists—blacksmiths, carpenters, carvers, steamfitters, and more. In 1888, the company was involved in a legal dispute with the Pullman Car Company over patent claims, and Pullman won. The competition between the two firms lasted until late 1899. After the death of Vanderbilt, the director of the Wagner Palace Car Company, the decision was made to close the business, and on January 1, 1900, the company was bought out by Pullman.

The Wagner house in Palatine Bridge was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973, and a monument in honor of Webster Wagner was erected in Fort Plain. He was also inducted into the Hall of Fame for Great Americans in the Bronx.

Wagner’s innovations laid the foundation for the development of modern long-distance passenger cars, and his name remains forever in the memory of travelers and in the history of rail transport.