In history, women’s work in science has not been widely covered, unlike that of men. Their successes have traditionally been considered less significant and necessary for society. Most of them received public recognition after their deaths. This story is about a Bronx resident Elizabeth Gertrude Knight Britton, a woman botanist to whom we all owe the creation of the New York Botanical Garden and the American Bryological and Lichenological Society. The i-bronx.com will tell you more about her life and work.

Childhood in Cuba

According to scihi.org and Sylvia Kinosian and Jacob S. Suissa in their book Mothers of Pteridology, Elizabeth was born in NYC on January 9, 1858. After her birth, her parents moved to Cuba, to the city of Matanzas, which is on the shores of the Florida Strait. It was here, surrounded by tropical Cuban greenery, that the girl spent her childhood. Her siblings, four of them, were always with her. Living in Cuba allowed Elizabeth to fully immerse herself in the island’s ecosystem and this had an impact on her botanical interests in the future.

Her parents were wealthy. They owed their wealth to the family’s holdings in industry and land ownership. Elizabeth’s grandfather owned a sugar plantation and a furniture factory. The money and life on the island allowed the girl to earn a degree in Spanish, which would later come in handy during her expeditions.

Education and formation of a scientist

When it was time to go to school, her parents first sent her to a private school in New York. During this time, she spent a lot of time with her grandmother. Then came the time to study at the Normal College or, as it was later called, Hunter College. This institution was designed to provide education only for women and it trained future primary and secondary school teachers.

At the time, this was the only way to get into science as it was a botany school, which she was fond of. Elizabeth graduated in 1875, when she was 17 years old. Her degree allowed her to stay on at the college (first as a critic teacher, and then as a natural sciences teacher) and begin researching, collecting and studying mosses. In 1881, she published her first scientific paper.

Ten years passed. E. G. Knight married Lord Nathaniel Britton, who at the time was an assistant professor of geology at Columbia College. The husband supported his wife’s interest in botany, and so she found in him a reliable ally and friend.

After her marriage, Elizabeth left college and focused on her research. She even had to take an unofficial (unpaid) job at Columbia University to manage the moss collections there and thus contribute to their study. Thanks to her activities, the university was able to purchase a valuable collection of mosses by the famous Swiss researcher August Jaeger for $6,000, and thus enrich its funds.

Scientific activity

Elizabeth’s desire to improve herself and learn more about mosses, lichens and ferns quickly made her a well-known personality in botany and, in particular, in bryology (i.e., the science of bryophytes, their anatomy, morphology, physiology and systematics).

Throughout her life, she actively researched and published data on such plants as Ophioglossaceae, Schizaeaceae, etc. The woman wrote a number of articles on Contributions to American Bryology.

The researcher also studied the relationship between fungi and other plants, created a catalog of West Virginia mosses and wrote about ferns (16 articles on this type of plant in total). The scientist made expeditions to Cuba, India, Nova Scotia (Canada) and the United States, including the Great Dismal Swamp, the Adirondack Mountains (New York), North Carolina and other places. In total, she made 23 trips out of 25 in which her husband participated.

During her lifetime, Elizabeth published more than 346 scientific papers (and these are only those attributed to her). Of this number, 140 were devoted to mosses. Also, 15 plant species and a genus of mosses (Bryobrittonia) were named in her honor.

Role in the Botanical Garden’s creation

Throughout her life of plant research, E. Britton became a recognized expert in bryology in the United States. Over time, she and her husband decided to create a Botanical Garden in New York. The idea did not come at one moment. It happened during a trip to England in 1888, where the family of scientists was sincerely fascinated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Its beauty, area, number of plants and library attracted attention.

Therefore, upon returning home to New York, E. and N. Britton began organizing a similar garden in New York. To do this, they attracted wealthy people of the city as founders: Cornelius Vanderbilt, Andrew Carnegie and John Pierpont Morgan (a metallurgical magnate).

Having received the necessary funds and land in the northern part of Bronx Park, they began to create the garden. The date of its foundation was 1891, when the state legislature (the Bronx was not yet part of the city) authorized the garden to be on the above territory. The estate of tobacco magnates Lorillard used to be there. There were 20 hectares of forest in the center of the garden. This is the largest remnant of the original forest that has existed there since the 17th century, when the first settlers arrived in the US.

The first director of the garden in 1896 was N. Britton. The area of the garden is 101 hectares or 250 acres. At the beginning of the XXI century, more than 1 million plants grew there. The garden has different landscapes, which is why more than 960,000 visitors come every year to see the living conditions of plants in the desert, tropics and temperate climates.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the garden’s botanical library (550,000 books at the beginning of the twenty-first century) was created in 1899. The herbarium (containing 7 million plants at the beginning of the twenty-first century) from Columbia University was transferred to the newly created site. A greenhouse was built in 1902. A separate room for roses was constructed in 1916.

In 1912, E. Britton was named the honorary keeper of the garden’s mosses (before that, she was just a volunteer and did not receive any money for her work). She held this position until her death.

The importance of her activities

Thanks to the activity of E. Britton, in 1906, materials collected by the scientist William Mitten were acquired for the garden’s collection. The woman wrote sections on mosses in the works published by her husband Nathaniel: Flora of Bermuda and The Bahama Flora. She was an advisor to doctoral students at Columbia University. Elizabeth’s work allowed her to create a number of societies. One of them is now known as the American Bryological and Lichenological Society.

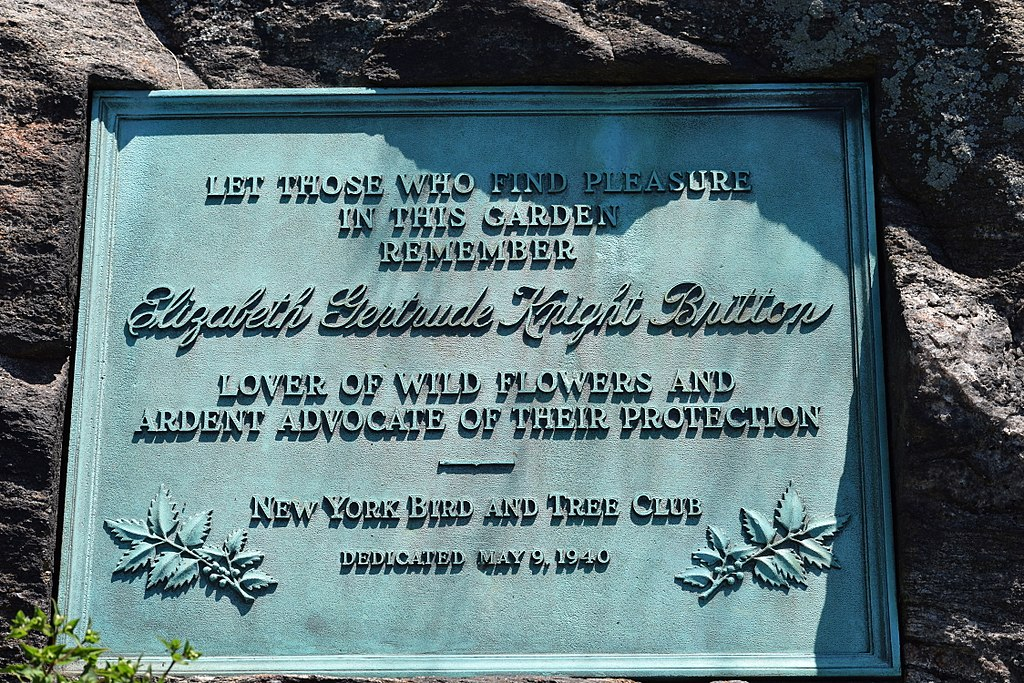

In 1902, Elizabeth invested $3,000 of her own money to found the Wild Flower Preservation Society of America. She worked here as secretary and treasurer. Thanks to the activity of the society and E. Britton, lectures were given, correspondence was conducted and legislation aimed at protecting plants in different states was adopted.

Thanks to Elizabeth, in 1925, a campaign was launched to boycott the harvesting of wild American holly, which was used as a Christmas decoration.

Death of a researcher

E. Britton lived for a long time in her home in the Bronx. It was there that she died on February 25, 1934, after suffering a stroke.